"Fast-forward into the future before making any expensive commitments" – Design Sprint

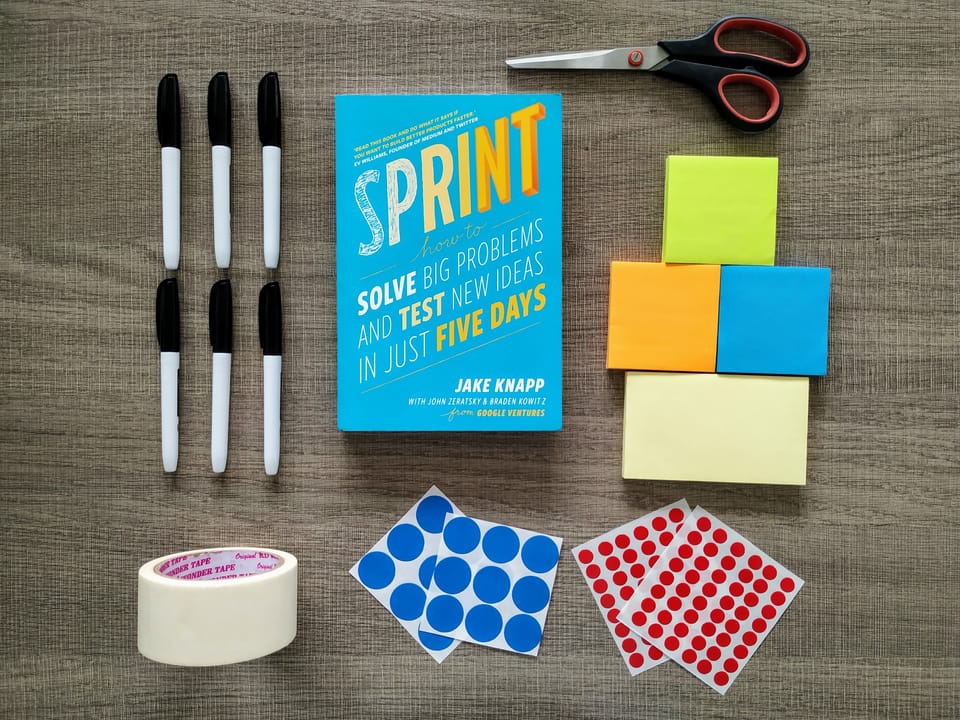

This article was originally posted in Medium. Photo by Gautam Lakum.

The first book I’ve read this year was "Sprint: How to solve big problems and test new ideas in just five days". This is a book written by three partners of Google Ventures on which they share a unique five-day process for solving tough problems, proven at more than a hundred companies.

I already knew a bit about the Design Sprint fundamentals, but I wanted to dig deeper. This is a great methodology when you are starting your start-up, when you are having problems finding product-market fit or when you are going to launch a different product. In summary, when the stakes are high and you need to learn fast. It’s not a day-to-day methodology.

You can find a lot of information on the The Design Sprint website so I’ll just share some interesting points.

The sprint gives our startups a superpower: They can fast-forward into the future to see their finished product and customer reactions, before making any expensive commitments. When a risky idea succeeds in a sprint, the payoff is fantastic. But it’s the failures that, while painful, provide the greatest return on investment. Identifying critical flaws after just five days of work is the height of efficiency. It’s learning the hard way, without the “hard way.”

You should always apply this philosophy. Learn as fast as you can, there is no need to develop. Your product designers and engineers must visit your clients 2 times a month and talk to them by phone every other day.

To build the perfect sprint team, first you’re going to need a Danny Ocean: someone with authority to make decisions. That person is the Decider, a role so important we went ahead and capitalized it. The Decider is the official decision-maker for the project. At many startups we work with, it’s a founder or CEO. At bigger companies, it might be a VP, a product manager, or another team leader. These Deciders generally understand the problem in depth, and they often have strong opinions and criteria to help find the right solution.

It’s key that all the company is invested on the design sprint, starting with the top decider, the CEO.

Sprints are most successful with a mix of people: the core people who work on execution along with a few extra experts with specialized knowledge.

Troublemakers see problems differently from everyone else. Their crazy idea about solving the problem might just be right. And even if it’s wrong, the presence of a dissenting view will push everyone else to do better work.

It’s funny how true this is. I’ve experienced many debates where someone proposed a crazy idea and in fact, it helped the debate making clearer what our end goal is.

We never accomplished significantly more than we did in a week. Weekends caused a loss of continuity.

We have a simple rule: No laptops, phones, or iPads allowed.

This is important, everyone’s mind must be focused on the sprint. It’s really hard for some people to disconnect, so it’s better to forbid electronic devices.

Monday

Monday’s structured discussions create a path for the sprint week. In the morning, you’ll start at the end and agree to a long-term goal. Next, you’ll make a map of the challenge. In the afternoon, you’ll ask the experts at your company to share what they know. Finally, you’ll pick a target: an ambitious but manageable piece of the problem that you can solve in one week.

Amy’s phrase “Remind us . . .” is useful, because most interviews include content the team has heard before, at some point or another.

This applies to all meetings. It’s important that everyone understands the concepts. I always use this technique “Remind us…” when someone says something I’m not sure other people in the meeting know about.

Tuesday

On Monday, you and your team defined the challenge and chose a target. On Tuesday, you’ll come up with solutions. The day starts with inspiration: a review of existing ideas to remix and improve. Then, in the afternoon, each person will sketch, following a four-step process that emphasizes critical thinking over artistry. Later in the week, the best of these sketches will form the plan for your prototype and test. We hope you had a good night’s sleep and a balanced breakfast, because Tuesday is an important day.

We know that individuals working alone generate better solutions than groups brainstorming out loud. Working alone offers time to do research, find inspiration, and think about the problem. And the pressure of responsibility that comes with working alone often spurs us to our best work.

Start brainstorming individually and then share those ideas. It works so much better.

We’ve used sprints with startups in all kinds of industries. One surprising constant: the importance of writing. Strong writing is especially necessary for software and marketing, where words often make up most of the screen.

Copy is so much undervalued!

Wednesday

By Wednesday morning, you and your team will have a stack of solutions. That’s great, but it’s also a problem. You can’t prototype and test them all — you need one solid plan. In the morning, you’ll critique each solution, and decide which ones have the best chance of achieving your long-term goal. Then, in the afternoon, you’ll take the winning scenes from your sketches and weave them into a storyboard: a step-by-step plan for your prototype.

Decisions take willpower, and you only have so much to spend each day. You can think of willpower like a battery that starts the morning charged but loses a sip with every decision (a phenomenon called “decision fatigue”).

At the end of the day you are more tired and the decisions you make are worse. Be careful of meetings or discussions in the evenings.

Thursday

On Wednesday, you and your team created a storyboard. On Thursday, you’ll adopt a “fake it” philosophy to turn that storyboard into a realistic prototype. In the next chapters, we’ll explain the mindset, strategy, and tools that make it possible to build that prototype in just seven hours.

Friday

Sprints begin with a big challenge, an excellent team — and not much else. By Friday of your sprint week, you’ve created promising solutions, chosen the best, and built a realistic prototype. That alone would make for an impressively productive week. But Friday, you’ll take it one step further as you interview customers and learn by watching them react to your prototype. This test makes the entire sprint worthwhile: At the end of the day, you’ll know how far you have to go, and you’ll know just what to do next.

It turns out it was an amazing idea, but to make it work, they had to do those interviews. “There’s this gap between the vision and the customer,” Joe says. “To make the two fit, you have to talk to people.”

For many reasons it is key that all the sprint members watch the interviews at the same time. This is the moment you have been working for all week. You are going to laugh, you are going to shout in pain and you are going to be amazed. In summary, you will get so many insights watching the interviews that it’s mandatory that everyone attends.

The Wright brothers didn’t use sprints to invent the airplane. But they used a similar toolkit. And they used it, and used it, and used it. Forming a question, building a prototype, and running a test became a way of life.

“It wasn’t luck that made them fly; it was hard work and common sense,” said Daniels. He went on: “Good Lord, I’m a-wondering what all of us could do if we had faith in our ideas and put all our heart and mind and energy into them like those Wright boys did!”