José Pérez-Agüera, Mercadona Tech CPO, on the analytical knowledge and tools Product Managers must know

Mercadona Tech is the tech company from Mercadona, one of the most known supermarkets in Spain. José Pérez-Agüera joined three years ago as CPO. We talked about the analytical skills and tools Product Managers must know and how their relationship with Product Designers should be.

There is one thing worse than not analyzing the data, and that is doing it badly. The data-driven approach is often demonized by flawed analysis.

Jose is a reference in the Product industry in Spain. In Mercadona, a very traditional company, he has successfully transformed their online experience while solving lots of internal operational challenges. Jose and I have been talking several times during these years as Ontruck and Mercadona face many similar operational challenges.

Meeting Jose

Jose joined Mercadona Tech three years ago as Chief Product Officer. He manages the product and design team for user-facing and logistic products. He helped them hire a great tech team, implementing a lean startup culture mentality and agile methodologies.

Previously, he worked as Product Manager and Product leadership roles in well-known startups like Tuenti, Jobandtalent, and Amazon.

A curious fact is that he studied History first, but he got tired that everyone expressed their view of history. So, he went for something more binary. He studied Computer Science, and he ended up doing the Ph.D. His thesis and first job in Yahoo! was about using Statistics and Machine Learning to improve Search Engines.

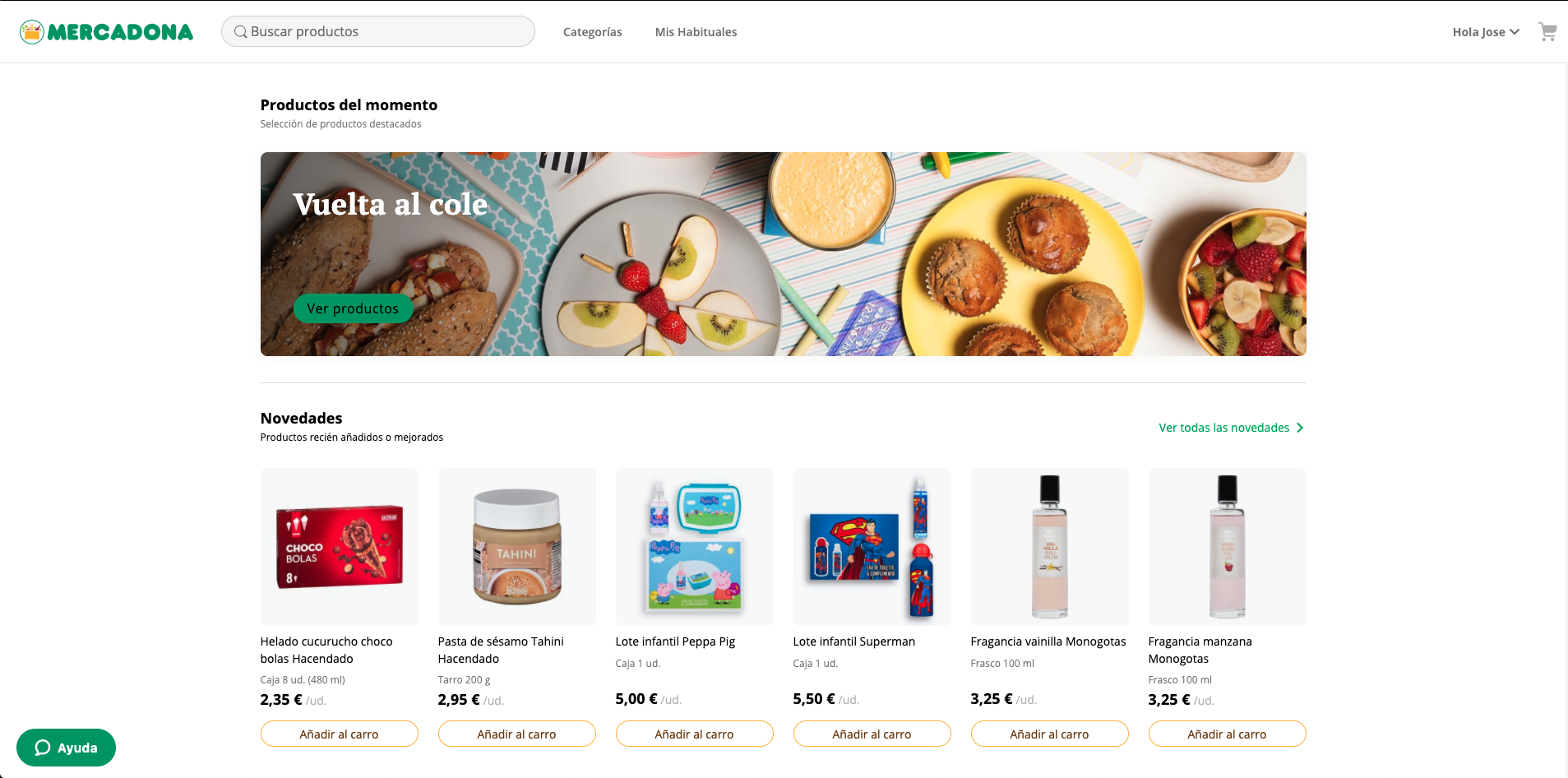

Meeting Mercadona Tech

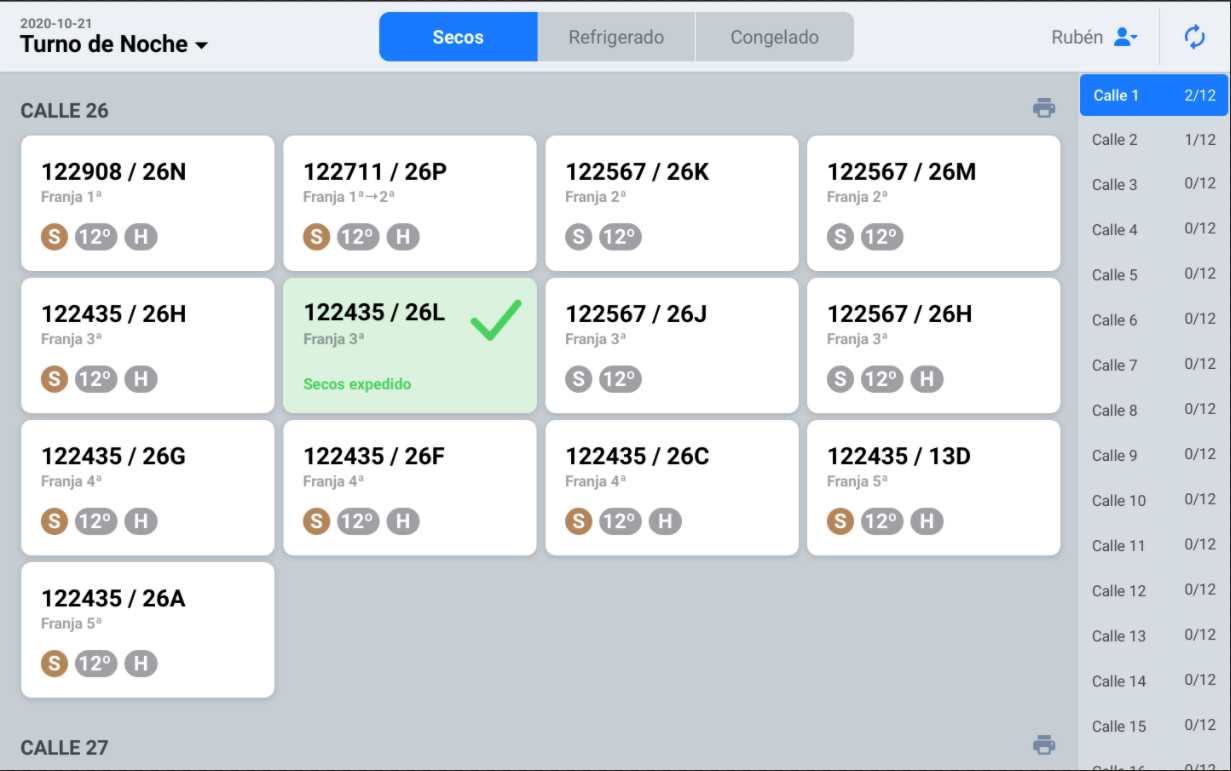

Mercadona finally decided to make a firm commitment to e-commerce in 2016. They decided to start from scratch. They set up a completely new product, tech, and operational team to create a simple and intuitive experience for their customers and a supply chain that aims at efficient logistics through technology. They believed the unit economics only made sense if they had dedicated warehoused with dedicated processes for e-commerce.

They built almost everything from scratch, their e-commerce, their picking software, their routing algorithms, their warehouse, or their customer care. This decision has made them expand slowly, but with substantial experience. They only sell through their new website in several Valencia, Barcelona, and Madrid neighborhoods.

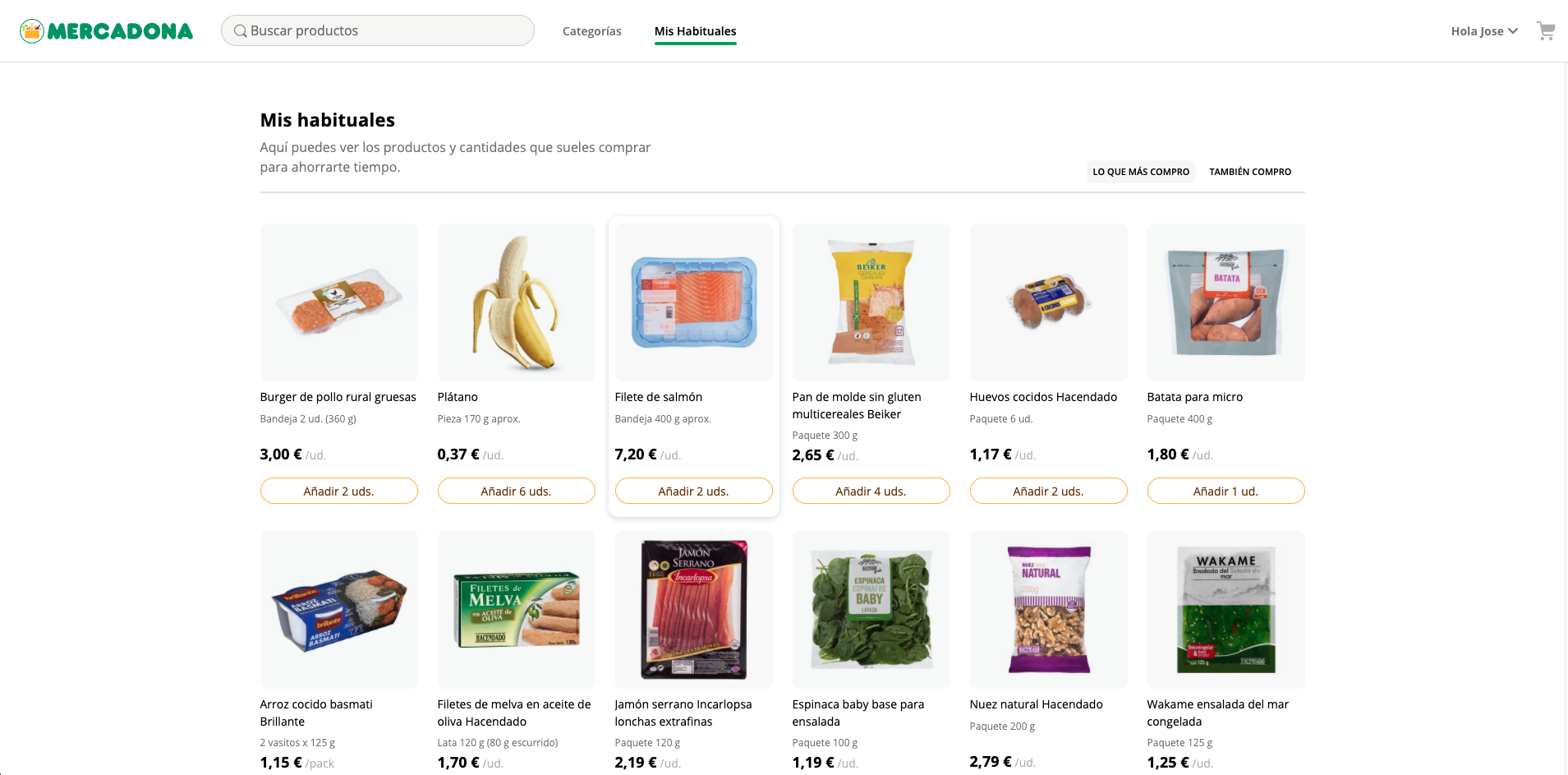

They are over 60 people in Mercadona Tech. They have three product areas: Warehouse (picking, supply and hive map), Delivery, and e-Commerce (including Customer Care).

Analytical knowledge and tools Product Managers must know in 2020

Jose starts strong the conversation. He believes we have forgotten to use the basic math we learned at school. Jose complains that now the most complex analysis you can ask a PM is a Pivot Table in Excel. In the first twenty seconds, he has made clear to me that he has strong opinions about this topic. Over our long conversation, Jose tries to sell me his vision of how Product should do analysis. He doesn't know I'm already sold from the start; that's one reason I wanted to talk to him.

It's funny how I have even fallen into the Excel trap. As Jose explains to me why an analysis isn't valid unless you have looked at the mean, median, standard deviation, maximum and minimum, I think that I haven't calculated some of them in 14 years since the Statistical course I took on my engineering degree. I even look back at my latest analysis from some days ago, and I wonder if I had committed any big mistakes. This interview is becoming a training for me.

He is frustrated because there is a double resistance: one to apply more complex mathematics and another to tools that may have a particular learning curve at the beginning but adapted to the casuistic needed in data management today.

Analytical knowledge

Jose is right; everyone of us studied the basic statistical knowledge needed in the school. Some of us even studied more complex techniques in college. So, why don't we see the connection between the methods we learned and our day-to-day work?

It is often frowned upon to see something mathematically complex because it seems that you are complicating it more. Commonly, people make decisions looking at the mean without comparing it to the median or removing their outliers.

Jose develops his thoughts "I have always found very poor to reduce someone's analytical skills to pure arithmetic. The mean is the worst metric; it hides everything from you. A mean is terrible. That's why I ask my team to start the analysis by describing the metric (mean, median, and standard deviation, maximum, and minimum). If the mean is one and the median is another or the standard deviation has a lot of dispersion, I no longer believe the analysis."

For example, the other day, I corrected someone at Ontruck because she said that the average time to answer was a certain amount of minutes. We didn't remove the outliers, so that conclusion was incorrect. Those mistakes affect the prioritization, the solutions we go after, and our users' experience.

He continues, "If I go a step further and ask you to represent the distribution of the data and I see that it doesn't follow a normal distribution, what conclusion are you going to take? You probably have a mess; you will get more conclusions by rolling dice than by analyzing that data". And he shares an example from Mercadona "The average cart is €130, what do you do with the user who has a €1,500 cart? What do you do if you have a minimum limit of €50? Do you know what's the deviation?"

Jose hits the spot. "There is one thing worse than not analyzing the data, and that is analyzing it badly. The data-driven approach is often demonized by poor analysis". He concludes, "present me clean data and then tell me your story."

Jose wrote the following article about some basic statistical techniques for Product Managers. I also recommend the following resource-oriented to Data Analysts, which serves as an excellent summary to improve your analytical knowledge.

Many of us may know to do great analysis, but definitively most of us don't have the right habits of analyzing them well. In the end, it is like programming or any other skill; either you do it every day, or you get stiff.

At Amazon, they forbid the use of quantitative adjectives as little, much, more or less. I haven't reached that level at Ontruck, but I may implement it as sometimes I'm frustrated with opinions like "this happens a lot." He continues, "When you make an effort to put a number to each quantitative adjective, first you see the difficulty, when you get into the habit you see the value, and then you never stop doing it." And that's when all your alerts go off when someone comes to you with a non-data-driven speech. This way of working gives the Product Manager a lot of clarity and focus.

Tools

Excel is still the king, but it no longer serves its purpose with the current data volumes. Jose is clear, "I don't think Excel is enough for the analyses that a PM needs to do today." For him, the standard is Pandas and Jupyter. In this environment, you can load 100M rows, and you can easily calculate means, medians, standard deviations, and transform the data to find the answers to your questions.

Jose worked at Amazon before Mercadona. Amazon is a very data-driven company; everyone knows SQL even. However, people keep using Excel as their primary analytical tool. When you use it with over one million rows, things start to break, and you start making a wrong analysis. The same analysis can be done in a few lines in Python.

He shares a recent example from Mercadona. They were analyzing the shopping list; they have 20 years of data and millions of rows. You can't do that analysis in Excel. On Pandas, it is solved in one hour with very few lines of code.

Jose seems to be alone in this way of thinking. Some people say asking PMs to know Python is too much; others say he is biased because of his Ph. D. Few agree with his ambitions.

I can understand why some Product Managers can be perplexed reading this. However, I agree with Jose's vision. As PMs grow and manage products that generate more data, they need to considerably improve their analytical skills. They can't rely anymore on pivot tables and looking just at means.

The reality is there are many types of Product Managers, and each company and stage has different needs. When you are starting, you need a PM who is better at discovering users' needs. When you're growing, you need someone great at prioritization and processes. When you are big and have lots of data, you will need someone very analytical.

Product Managers need to do the analysis

Can the Product Managers rely on their Data Analysts to make up for their lack of analytical skills? Both of us agree that's a bad idea. An analysis is a conversation with the data, and the PM needs to be the protagonist. If you want to understand the problem well, you must understand the data well. It isn't easy to do it if you have not done the analysis.

Jose shares one of those moments of self-frustration. "Some years ago, I had a fantastic Data Analyst in Jobandtalent, who did a complex analysis for me. But I had to do an exercise of faith because analyzing the data is a conversation with the data. As I discover insights, I keep asking questions. I don't know where I'll end. That is why Jupyter is so useful because you are talking with the data, and according to what it's telling you, you keep analyzing."

When Product Managers don't do this exercise, they don't leverage their qualitative knowledge to find quantitative insights. They can also not explain the problem well to those who have to solve it and guess the type of solution needed. And lastly, the company will need to teach the PM, PD, and engineers to challenge the conclusions from Data Analysts.

PMs need to be their own data analyst. Jose concludes, "I don't want to know anything about a PM who doesn't know SQL. It is a must. We don't have Data Analysts."

The role of Data Analysts

So, what do Data Analysts must do then?

I shared with Jose my own experience at Ontruck, and its mistakes after several years of fast growth. The situation we had at the beginning of 2020 was that we had a good team of four Data Analysts, which were mostly focused on getting data and doing dashboards for Business and Product teams. They were adding value, but we weren't getting the most out of them. We had over 800 dashboards, which only 40 were regularly used. Non-data analysts couldn't get the data by themselves. We didn't have a single source of truth, each dashboard got the data using different queries; so there were mistakes and inconsistencies. Business and Product people started to distrust the data and the insights we were getting.

When the Data team started to report to me in March, we reviewed where we were and what was blocking us from reaching our data vision. We took several decisions:

- Build a unique source of truth. We would accelerate creating Facts and Knowledge Layers to represent the primary data on our Data Lake. We would bring more data from external services (e.g., Zendesk). We would leverage the work of our Data Engineering team, which we hadn't used much.

- Focus on self-service. We opened the Knowledge Layers to the rest of the company in Tableau (business) and Superset (product & tech), and train them to get the data and create dashboards on their own. We forced Product teams to get the insights and track their features on their own.

- Kill and unify dashboards. We hid 600 dashboards overnight (we just received one complaint). We worked with management and the different countries to have a unique dashboard per business function, which uses data from the Knowledge Layers instead of independent queries. Each dashboard is like a product; its quality and UX must be reviewed and iterated.

Almost six months later, the situation has completely reversed, and now, we are going in the right direction. Data Analysts have taken control of their time. They will soon focus on complex analysis, which is where they can provide the most significant value to the company.

Jose adds, "I see it in the same way, but not all business people see it in the same way. There is also resistance from some PMs. It is a shame that the Data Analyst becomes the person who makes the dashboards because if you give them space, they can make a fascinating analysis. Following that approach is even more difficult when the analysts are junior because they have the perception that their job is to obtain data for business. And if they go that direction, they become passive people, not reactive. And they should have their space for proactivity."

You can read more thoughts from Jose in the following article.

The relationship between Product Designers and Product Managers

We have invested and shared a lot at Ontruck, so Jose was very interested in this topic. He didn't have great experiences on his previous jobs, so he has had to learn from other companies.

He remembers that during his experience in Tuenti in 2012, the designer's role was incredibly underrated. The designer was only visual. The industry has evolved a lot, from outsourcing design to having the Product Designer at the same level as the PM and Engineer Lead. Product Designers have gained much more strategic weight.

Amazon is so data-driven that there is almost no qualitative. You can feel it when you use their website and products; they lack user experience. Jose didn't fit there, as many other Product people have experienced. "No matter how much the quantitative tells you, it is not opening the door, it is not telling you why. You are only going to get it from the qualitative".

He has very clear that "the magic is that the data tells you the same as the qualitative analysis. You must use the best of both worlds, what is happening, and why it is happening. That's a good starting point to start thinking about solutions". Product Manager and Product Designer complement each other, bringing two different perspectives, so they should make each other participants of their analysis. If you add the engineering leg, you have the perfect triangle to build very robust solutions.

No matter how visionary is the PM, they need a solid Product Designer focused on product, not so much on design. Jose thinks Product Designers have to accept that they are going to design fewer interfaces. PDs need to improve the lives of their users, either with an interface or with processes. A process has to feel as usable as a great product. If a designer doesn't do that, they will be another type of designer but not a Product Designer.

Soft skills in Product Designers

Digging into what makes a great Product Designer, Jose acknowledges that the challenges usually come related to soft skills. And the biggest one is that the PD is genuinely open for feedback. This is precisely one of the areas where we invest more at Ontruck.

Jose explained it this way "The most comfortable way to work is not to ask anyone for an opinion, so they do not challenge you. In that environment, your ideas will receive many more challenges later; it is a more uncomfortable environment because you are more questioned. There is going to be more friction".

I agree with him. My impression is that someone is senior when it's open for feedback. The defensive position is a consequence of insecurity; it's a junior mentality. Seniority gives you peace. Transparency is essential to build great products in teams, but it exposes you. And not everyone is ready to receive that feedback. This feedback can be applied to any role. I see very clearly in Product Managers when they delay the communication or sharing their decisions to avoid receiving feedback and confrontation.

If you fall into this error, I suggest you practice active listening. It's one of the soft-skills that will help you more in your career and personal life. It is very comfortable not to listen to others, but you won't get far.

An hour and a half later, we closed our conversation. We started talking passionately about data and Jupyter, and we ended up talking about soft-skills. It's a good summary of how complex the role of a Product person is.